Lessons Learned from Competing in an Overcrowded Market

In this Article

-

- What we’re doing differently moving forward

Lessons Learned from Competing in an Overcrowded Market

At DemandMaven, we just wrapped up a project for a client that was in one of the most competitive markets.

While we had some incredible wins, we also had many lessons learned — some of which I wanted to document and share here. I don’t want to be one of those marketers who only tells the rosy, glossy stories of growth and marketing.

Social media and content often becomes limited to just being a highlight reel: you only see the good stuff.

But there’s also a time and place for talking about the hard stuff, too.

Here’s our lessons learned from competing in an overcrowded market.

For context, our extremely crowded market was project management. Productivity software, in general, is both extremely competitive and yet consistently attracts more SaaS apps to the space.

This wasn’t my first rodeo in regards to competition. Quite the contrary — most of my experience has been competing with 3-5 other products at a time, all striving for significant market share.

What made this experience different was just how competitive the productivity space was in addition to having a few 800 lb. gorillas with clear market share and longevity in the market.

“Competitive” doesn’t even quite feel like the right word because “competition” is only indirectly felt. You might hear about a customer leaving your product for another solution; perhaps you hear in a demo that you’ve been compared to another product or way of accomplishing the same goal.

We were competing in the project management space which easily holds hundreds of products with a few key 800 lb. gorillas — Asana, Trello, Monday.com, and Basecamp to name a few. And pretty much every single demo or customer interview revealed the dozens of products the prospect or customer had considered throughout their buying process.

Yeesh. What on earth was our foothold going to be in a market like that?

The 6 basic principles of competing in a highly competitive market

Hindsight is always frustratingly 20/20. Knowing what I know now, if you’re going to enter a market with a total addressable market (TAM) of $1B or more with 100+ competitors, there’s a few things you’ll need to do differently than if your TAM was $100M with no competitors:

- You’re going to need a clear, competitive differentiator. This differentiator is what makes you different, better, and special. It sets you apart from everyone else. Maybe you’re tackling a specific pain for a specific audience better than the other guys.

- It’s going to have to actually be better than all of the other competitors. “Better” is also not as cognitively clear because to almost every founder, their product already is “better”. But it has to be recognizably “better” to the customers as well. They’ve got to feel that “betterness”.

- If it’s not better, it’s going to have to be a little cheaper, although some would argue this would need to be the case regardless as a new player in a highly-competitive market.

- Have zero friction to signing up and becoming a paying customer. It needs to be pretty easy to make a decision about the product and actually sign-up. Some would argue that adding barriers to entry would increase demand, but that totally depends on how many competitors there are and how frictionless they appear to be. Time to value is also a critical component when weighing how to approach this. The longer time to value, the less friction you’ll need to have.

- Find a channel with the most opportunity. If you’re in an extremely crowded market, then it’s likely that most acquisition channels will be tapped (and maybe maxed out with extremely high CPLs). You’ll need to follow basic rules on ARPU and adjust CAC accordingly, but after that, prioritize the channels you can either beat the competition at, are totally untapped, or both!

- Lean into your strengths skill-wise and resource-wise. This one’s a tough one because they’re not always obvious and it seems like a weird thing to list. But knowing the competitive landscape, you’ll need to identify what you can provide that’s better and different from a marketing perspective. So if you’re good at speaking, networking, writing, building, whatever — leverage that because it (usually) can’t be copied. All of that, of course, within the context of what your buyers are most likely to do, consume, and care about.

These 6 basic principles are really just the start, and to be honest, we only did a few of these extremely well. Our clear, competitive differentiator started as a few features that later became our vision. Eventually it became the thing that our customers raved about.

It’s tough to say, however, if the product was actually better in a global context. For example, many would say that Clubhouse is a clearly superior alternative to a tool like Asana if you were using it to manage software development — with software development being the context. Asana wasn’t built for managing software development to the extent that Clubhouse covers the need.

Our product was clearly better when pitted against the big players if you wanted to be able to automate your tasks and workflows and build processes that scale across many different departments, and if you managed the same processes over and over again.

Through customer research, we discovered that some of our absolute best customers were also still using competitive solutions for other teams and contexts. So were we better? Yes, but for a very specific kind of problem. We couldn’t cover every base, however, and I don’t know that it would have made sense to (focus being the prevailing wisdom, here).

Competitively-speaking, the big players had everything except for the one thing we did absolutely best for just about every vertical. Beyond that, we had to make a few bets on what we could do growth-wise that the other guys either couldn’t do, or weren’t doing very well.

Making your competitive bets

The best way to evaluate this would be across the four main quadrants according to Brian Balfour: product, market, model, and channel.

And then, of course, layer in with what we already know to be true about growth. There’s 5 main growth levers according to Katelyn Bourgoin:

- Increase general awareness — harder to measure, but this could be brand awareness or problem awareness

- Increase in website traffic — drive more traffic month-over-month to the website from various channels

- Increase in leads — generate demand for the product through sign-ups, downloads, etc.

- Increase in sales — improving conversion rates, increasing revenue per user, total sales, etc.

- Increase in capacity (team) — hiring more people to do more

After following the main 6 principles to competing in an overcrowded market, identifying our best bets and prioritizing our main growth levers, we can finally start building a go-to-market strategy that’s going to give us the foothold that we need.

And the cool part is, we just need to get over The Wall, like, once to learn what we need to do next.

Using guardrails to guide growth

A business can navigate their growth in a few ways, but the first is to put “guardrails” or a “baby gate” on the TAM. Imagine trying to go after the entire market all at once. It’s similar to boiling an ocean: unless you’ve got bookoos of dollars, it’s going to take forever and you’re going to get overwhelmed.

The total $1B TAM is really only the focus after we’ve hit significant traction and can expand the go-to-market team. But to start, we focus on just one specific segment in the market. A great example of this is actually Nathan Barry of ConvertKit. He took his TAM and broke it down into a segment that he could market and sell to immediately and later expanded his focus as he found product-market fit within certain segments.

The problems we had with this, though, was we never really doubled-down on any one particular segment, and we never committed to building the product specifically for any one segment either. There’s a few reasons why that I won’t get into here.

We stayed broad in the project management space, and I firmly believe that was to our detriment. It meant that we built broad, and while it’s amazing to build something that solves many problems across many verticals, it made our go-to-market strategy equally as broad.

Unless you’ve got an insane amount of capital, staying broad becomes insurmountable if you’ve got hundreds of other competitors scraping the same sides of the can as you are.

You can try to carve the market by focusing on one segment at a time (and that’s absolutely what you should do with the right resources and a product that solves a BIG problem for a big market), but even that makes the assumption that:

- They care about what you have to offer

- You can align your product messaging fast enough

Instead, I recommend one of two approaches:

- Enter the market with a clear vision (even better if for a specific group of people)

- If you don’t have a clear vision, implement a growth strategy that enables you to learn as much (and adjust) as fast as possible.

Let’s dig into each, shall we?

Option A: Enter the market with a clear vision

It’s rare, but some founders build products with a very specific audience and market in mind.

That’s not to say this group outperforms the other group; on the contrary! Plenty of products are built for a particular audience and discover too late that it was the wrong product.

But every now and again, a founder will do extensive research and build a specific product based on the pain of a particular part of the market. Again — that’s not to say this approach is strictly “better” because even this can fall flat. I want to be careful here. Building a business is hard, and there’s many ways to do it.

It certainly decreases the risk, however. Typically these founders build an MVP with a specific vision in mind: to eliminate a particular pain for a particular segment of the market.

If they make good product bets and do their research well, they end up with an MVP that is pretty sellable as-is. From there, it becomes more about catering to a specific audience and continuing to expand and align the vision.

Like I said… these examples are extremely rare.

The only that comes close is actually a current client of mine: Motivo. Before ever even building a product, the founder built a service offering first and productized it later. The audience and the pain were always focused; it was just a matter of if a product could be built that could later scale to solve the global pain within the clinical supervision world and if there’s a model that could be extremely profitable and serve as a win-win for the audience.

However, if you don’t have a specific vision for the market or the problem, that’s fine. It just means your approach will likely do a little bit more meandering and a whole lot more experimentation on the market and the product.

That brings us to Option B…

Option B: Implement a more informed approach to growth

This is a far more common scenario across the board, and 9 times out of 10, exactly what more founders experience.

They identify a pain in the market and decide to build a product for the market, but they know it’s a larger pain that can be solved across other segments as well. Sometimes the mission is to tackle a BIG problem in a BIG market, and sometimes the founders just want to find their niche and double-down on that once they find it.

A great example of this approach is a well-known one: Convertkit. Nathan didn’t just wake up one day and was like “I want to create an email platform for creators”. It took him several years to arrive at the focus that his brand has now.

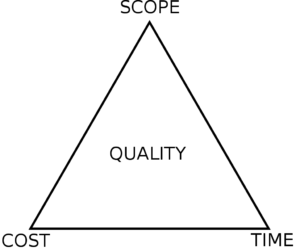

This introduces a critical component to this approach however: you need to implement a growth framework that allows you to do either find your niche and/or solve a BIG market problem within the constraints of your competition AND scope, time, and budget (or the “iron triangle” as the COO from my first role used to always say).

Your go-to-market strategy, in a way, kinda depends on what your own personal goals are for the business as well. So, naturally, you’ll need an approach that helps you arrive at the right conclusions to make better decisions moving forward.

We tried to do this with the project management product I mentioned earlier. While we had a few wins, it took us way too much time to learn from our mistakes and get there — especially given the competitive market we were in.

Looking back, I think we should have brought product to market much differently, especially if we wanted to stay broad in order to explore our options. This is how the framework probably should have gone:

- Raise money pre-product

- Launch with a freemium (if possible)

- Implement paid plans over time

- Remove as much friction as possible

- Re-position with more customer feedback and data

- Invest in channels according to ARPU

Strategy 1: Raise money pre-product

I can feel the hissing from across the screen. Some of you are violently against raising venture capital, and I totally get that.

But when you’ve got a market that’s absolutely huge, an extremely competitive landscape, and a product without clear PMF, then it becomes a “whoever is loudest, wins!” game really fast.

I don’t think it’s necessarily required to raise a bunch of money to compete in an overcrowded market, but we’re all beholden to the iron triangle of scope, budget, and time.

If you didn’t care how long it took to reach your goals, then you could go about your merry way and budget and scope don’t really have the same pressures. But if you wanted to reach $1M ARR in 2 years, then you’d likely need to get the budget and blow out the scope in some way.

Otherwise, we need to go back to Option A and think long and hard about who we want to to serve and why and what product we should actually build.

If we want exploration, however, and the ability to choose, it likely comes at some cost and we’ll need to calculate that.

Strategy 2: Launch with a freemium

Freemium is a scary word for founders. To be honest, it was even scary for me until it became painfully obvious that most of the market expected some sort of freemium plan in the project management space.

A freemium plan does two things:

- It allows you to learn as much as possible since it has low-risk

- Builds your awareness

Many experts agree that “freemium” really isn’t a revenue model to begin with, but it certainly helps with acquisition and product development. And if you’re in an extremely competitive market where achieving feature parity is unlikely and freemium is expected, then you might strongly consider it.

In our case, we were never going to “catch up” and achieve feature parity in time with the other big players, and the big players have the majority market share anyways. If we want market share in our current landscape, then our mission would be to generate as many users as possible with the goal of identifying a niche that we compete for.

But of course, that’s only if we stay broad. Nicheing would have lended a different strategy and probably put us in the Option A category, but even here, I think we still would have launched with a freemium, saw the behaviors of our customers and existing patterns across the entire base, and focused on a segment that had clear product-market fit.

Freemium comes with its own risks, of course, but only if we think of it as a permanent plan.

Strategy 3: Implement paid plans over time

Let’s assume we did step number one and “freemium” is clearly not the way to go. You should still hold off on implementing paid plans — at least for a little while.

Many businesses launch with an unpaid beta plan and roll out paid plans over time. I actually like this approach a lot when thinking about the competitive landscape. If it’s an overcrowded market, rolling out paid plans over time allows you to:

- Grow your user base

- Identify the most critical product features across user segments

- Study the way other products are priced in the market

- Launch a paid offering that is both fair and competitive

- Still niche down when a prevalent segment reveals itself (if that’s the plan)

I don’t have a perfect science on “when you hit X users, launch your paid plans” because it will be totally dependent on the feedback you get from users.

It does, however, imply that again — you’ve got the scope, time, and budget to successfully do this.

Strategy 4: Remove as much friction as possible

It probably goes without saying, but I think it needs to be said again. It should be ridiculously easy to sign-up for the product and get value from it.

Not every product can achieve this, however. Some products have natural friction built into them. Others take a while for users to experience the value. In these cases, there’s a few ways to think about it:

- If the product has a shorter time to value, remove as much friction as possible to sign-up or try the product and tighten up the onboarding

- If the product has a longer time to value (i.e. several weeks or months), then remove friction, but introduce more whiteglove onboarding

This brings us to product complexity — which is probably a whole other post, but the more complex your product, the more likely you or the team will need to be involved in helping the customer achieve success.

Generally speaking, we only introduce friction when we:

A. need the user to understand something critical to receiving value and/or

B. disqualify users from entering our pipeline or becoming a paying customer (and therefore churning later because they’re not good fits).

The irony of this is that if you’re in Option B in a competitive, overcrowded market and want to learn as much as possible, then we’re assuming that you want to explore your options as much as possible. You’d likely not introduce friction without the explicit intent of learning something or improving the experience.

There are some strategies that incorporate a little bit of friction when signing up to increase the demand of the product and/or to solidify product-market fit (think like Superhuman’s extensive invite-only and qualification process).

However, I’d argue this works best with incredible market focus — even if they are solving a BIG problem (email management), they’re still competing with free products that are distinctly “not better” which satisfies all of the 6 basic principles mentioned earlier.

When I began working with the client, they had already launched with a pretty basic 21-day free trial, but they required a credit card to sign-up. At the time, it generally made sense.

People who were high-quality and weren’t tire-kickers would be the ones who would sign-up thus improving our overall funnel metrics and only highlighting the quality people. That remained pretty true, but growing the net new leads month-over-month became increasingly more challenging as we started to explore different segments.

The overwhelming lesson learned was that if the market generally didn’t expect to enter a credit card to start a trial, then why would they waste their time signing up for our product?

It was too easy to bounce from our funnel and sign up for Monday, Asana, or Trello for free without any friction and a freemium account. The perceived benefit of entering in the credit card would need to outweigh the friction of doing so, and I don’t know that it’s easy for a new challenger in the market to make that clear with so many free and easy competitors to fall onto.

We, admittedly, spent 13 months with a required credit card in our funnel, and I still regret every month of it.

When we finally did remove the required credit card, the results were instantaneous. Churn dropped from 40% to 4% and net new free trials tripled overnight. Our free trial conversion rate, however, suffered, but it became clear that customers weren’t converting on their own anyways.

They were just forgetting to delete their credit cards from their accounts.

Strategy 5: Re-position with more customer feedback and data

After learning from the market as much as possible and growing your user and customer base, you’ll need to identify the best segments based on the data and feedback you receive. Ideally, you’d then re-position the product based on this feedback.

Convertkit, again, is a great example of this. They spent the first few years broadly going after the market until realizing that bloggers and content creators were the way to go. And even then, they focused exclusively on food bloggers to start.

You need customer volume to do this, however. The trouble with positioning is that it’s tough to do without the customer base. April Dunford, SaaS positioning guru and a dear friend, would probably say that it’s impossible, or perhaps, that it’s definitely not recommended.

The best you can do is start with your early-stage positioning and best guesses and further refine it after getting a significant base. A significant-enough customer base isn’t exactly defined (how many is tough to say), but once you have around 100 paying customers, you’d need to evaluate your customer base and do some form of positioning research based on the best paying customers.

With my client, we were hitting the wall against the same conundrum with pretty much every single churned customer and demo we had: we either didn’t have enough features for people looking for pure project management (no feature parity), or they couldn’t justify the cost of the product compared to other market alternatives (cost outweighed the benefit).

April Dunford’s book came at the perfect time.

This was especially true when we focused on project managers and small agency owners. As soon as we evaluated our positioning and launched our new messaging, that’s when we saw the 30% lift in MRR and it felt like magic.

Our positioning efforts weren’t perfect, however. But it was certainly a start. It gave us the pulse-check that we needed.

Strategy 6: Invest in channels according to ARPU

Your average revenue per user (ARPU) is somewhat of a damning number.

Don’t respect it, and you’ll spend more to acquire customers than you’ll actually make. If you don’t figure out how to increase the ARPU over time, then you’ll likely be stuck focusing on content marketing and SEO for forever until a more cost-effective channel comes along.

We can actually use the ARPU, however, to prioritize channels. For example, if you have a lower ARPU, then you’ll likely need to invest in channels that have a lower cost to acquire a customer (CAC). If you have a higher ARPU, then we can probably spend a little more to acquire customers (like paid acquisition and other means). If we have a really high ARPU (in the hundreds or thousands, for example), then investing in sales probably makes sense.

This is good advice regardless of your competitive market, and you’ll do a few things that don’t scale or are cost effective anyways in the beginning stages of the business.

When you add on the layer of an extremely competitive or overcrowded market with clear market leaders, however, then a few things impact the channels you invest in:

- If you’re able to find a niche — upon which you’d focus on the customer segments that are the most profitable for you and their market channels

- If you’re able to uncover untapped potential —upon which you’d focus on the channels that a) aren’t crowded, b) actually tap your target market, and c) are cost-effective

- If you’re able to acquire enough funding to effectively compete (with respect to your ARPU) — for example, you likely won’t outspend your 800 lb. gorilla competitors, but you’ll at least be able to pay enough to acquire leads at a CPL that makes sense

Basically, you’re either able to go head-to-head with you competitors and can afford to, or you can’t, and you’ll need to find other options based on your target audience. That brings us back to putting the baby gate on the TAM, but if this isn’t possible, then we’ll need to chart our path accordingly.

What we’re doing differently for clients moving forward

So what does this all mean for DemandMaven? And how do we identify these things and adjust our strategy according to what we find?

Well, as my friend and fellow agency owner Andrew Askins says, “It’s only a lesson learned if we truly learned a lesson.”

Moving forward, we’ll ask a few specific questions to founders who want to enter competitive spaces with or without significant funding:

- What’s the vision and the mission for the product?

- Do you have an audience in mind?

- Are you open to focusing on a specific audience?

- Are you open to making changes and adjustments to the product, the model, the market, and the channel where appropriate?

- How do you feel about being a spokesperson on behalf of the brand?

The questions will help us serve two purposes: level set with the founder on expectations, and identify which path the founder prefers to take.

Are they really taking Option A and have a clear vision in the marketplace? Or are they expecting flexibility and experimentation as they go-to-market and would prefer Option B?

It also forces us to get real about what’s possible and realistic given our time, budget, resources, and scope of what we hope to achieve in the market that we’re in.

As for us on the marketing-side, we do more due diligence in regards to the client’s TAM and competitive landscape. A highly competitive landscape and a TAM of $1B forces us to think about our growth path much differently than if we were in a $50M TAM and competing with spreadsheets.

We’ve adjusted our SOPs and sales process to address these questions when it becomes clear we’re entering a competitive market and also adjust our strategic investments accordingly.

Many critics of strategy and strategic efforts would heavy sigh at the amount of competitive analysis it would take to emerge with a go-to-market strategy and plan that could ensure the success of the business.

But if it reduced the risk of wasting time, energy, and resources, then why wouldn’t you?

✨